Forging new institutions and alliances for metascience

A Metascience 2025 keynote address

As an editorial in Nature put it, “On 2 July, a science initiative was born in a lecture hall in London.” That morning, the Metascience Alliance, a collaboration of dozens of organizations in the metascience community, was announced onstage at the Metascience 2025 conference.

We were honored to be invited to join the coalition at its launch and to speak at the conference, which brought together 830 participants from around 65 countries.

Anastasia Gamick, our co-founder and President, gave the opening keynote for that morning’s session, “Forging new institutions and alliances.” You can read it below.

–

Hi everyone - welcome to Day 3. I’m impressed that you’re all warriors and you’re all here this morning!

I want to flag that I’m not an academic - I’m a builder or an entrepreneur. I don’t often cite papers, and I don’t actually often read papers, but I wanted to bring a couple to share with you.

The first is an important piece of research published by a single author and it points at a really critical opportunity.

The second, Many Labs, represents the moment psychology turned a statistical warning into an operational solution - a publicly auditable, institution‑backed, globally collaborative stress‑test of its own evidence base.

Now, I asked GPT if the ManyLabs results would have been possible without various members of that alliance. It said:

“Without COS’s purpose‑built Open Science Framework and its central coordination staff, the dozens of labs involved would have had no common platform, or logistical backbone, for preregistering protocols, managing data, and synchronising a global replication effort.

Without the Registered Report format, participating researchers would have faced high career risk that null or contradictory results would be rejected by journals, stalling Many Labs at the proposal stages.

Without Arnold Ventures’ early multi‑million‑dollar grants covering staff salaries, servers, even the supplies that got shipped all over the world, the volunteer‑driven vision behind Many Labs would have lacked the material resources to move from idea to execution.

I would argue that ManyLabs is an example of how novel institutions and alliances are critical for many, many novel outcomes and experiments that we want.

At Convergent Research - we are busy creating one new type of this novel type of institutional types.

How many of you have heard of FROs? Cool!

We’re inspired by the large-scale science projects that created the fundamental capabilities needed to change fields, like the Human Genome Project, the Large Hadron Collider at CERN and the Hubble Space Telescope. These are examples of grand projects that were pivotal in accelerating their fields and that produced critical research resources. They were platforms that teams of biologists, astronomers, and physicists built on for decades after they were completed.

But, such large-scale projects are often once-a-decade efforts. They require huge feats of coordination and capital and consensus. The Human Genome Project, for instance, cost the federal government $5.6 billion in 2010 dollars and took almost 13 years to complete.

That’s large-scale science.

But what about midscale science?

Across every field, there are problems that are not easily solved within existing institutions, like corporations, venture-backed startups, or academic labs. These problems cost more than the typical NSF grant, in the range of tens of millions of dollars. They often have a bad dollar-to-paper ratio. You require engineers and many different scientists across many different areas, and you try things over and over again as you try to get to something that is executable and not just publishable. And because there is no existing institution, or there are very few institutions to solve these problems, they have been stacking up, choking off many fields we look at.

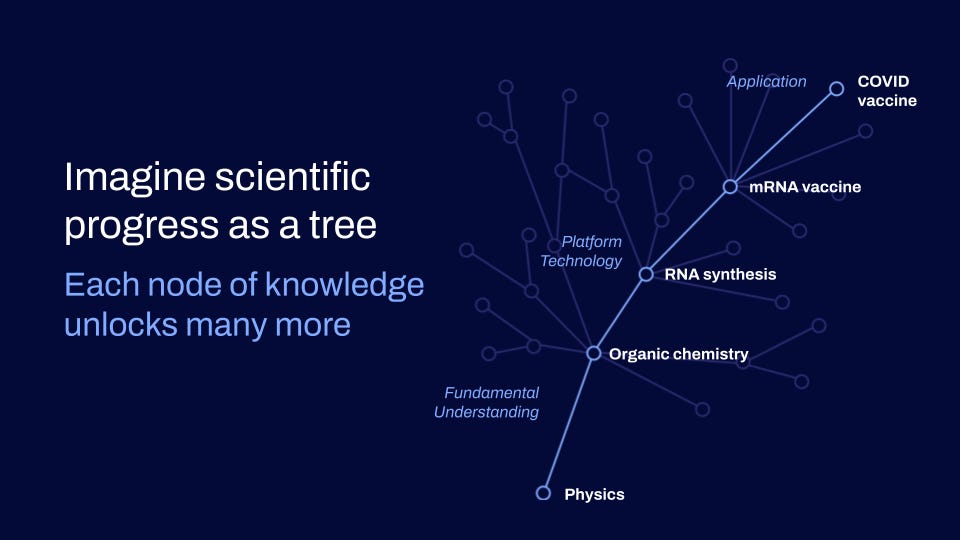

Here’s one way that we look at it.

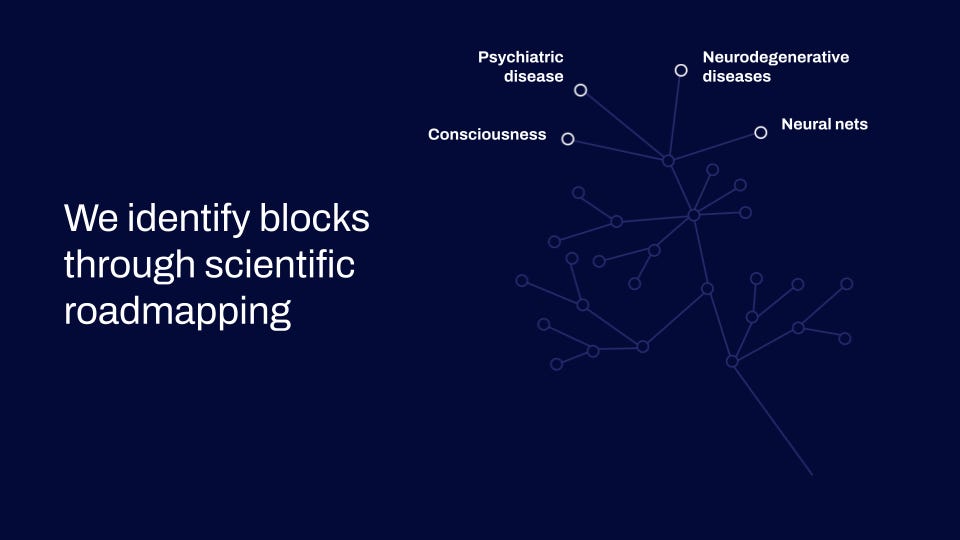

Imagine that science is a tree. And that progress goes from the core of that tree, where it’s a very core understanding - something like math or physics - out to the branches, where the fruit are the things that we use in our everyday lives. Let’s say that you want the fruit of that tree, something looks like curing psychiatric disease and neurodegenerative illness, training better and more aligned neural nets, answering deep questions about consciousness.

All of those fruits may depend on the existence of a single branch of science that is not mature enough or advanced enough to bear those fruits. It just might not exist.

In the case of understanding all of these things, we probably need to understand the synaptic connections of the brain. How do different neurons talk both to their neighbors and to neurons all the way across the brain to do things like reward signalling? And often, for that branch to exist, it often needs to come out from the trunk of the tree, and there basic tools and machines that exist at the center of science and technology to support that branch.

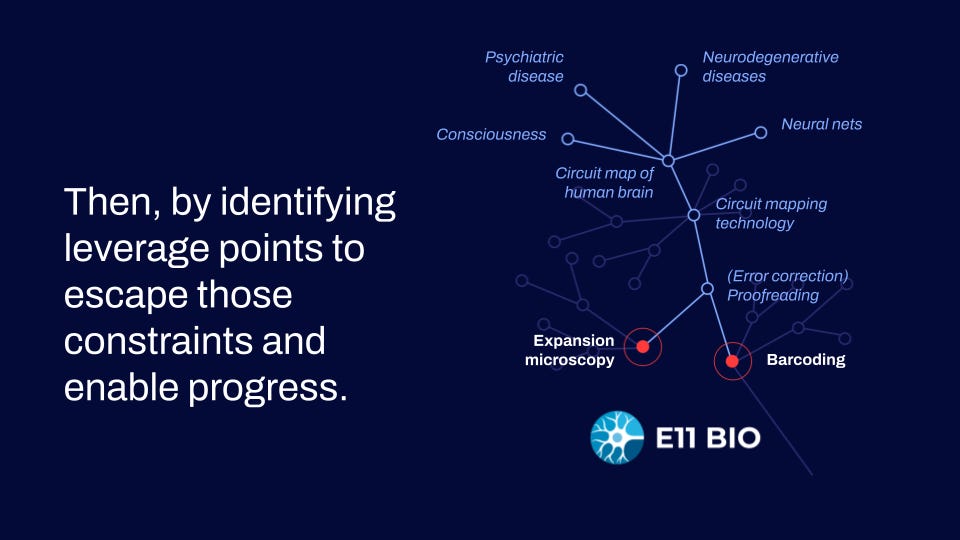

If you follow all the way back you come to something we call a fundamental capability. In this case of connectomics, it is reading and error-proofing the synaptic connections in a cheap and scalable way. And so we identified a couple of pieces of technology that would be really important to scale neuro-connectomics, and we built an FRO to tackle just those problems.

Soon, E11, which launched in 2021, will be releasing a preprint with data and the outline for a technology that they’re calling PRISM, which should enable scaling connectomics at an order of magnitude cost reduction from what was previously available.

[ed. note: This preprint, along with plasmids, reagents, and code, was released by E11 yesterday!]

Like all our FROs, E11 is doggedly focused on its particular goal. They want to unblock progress further on in the tech tree, and so they are pursuing pre-specified, quantifiable technical milestones that lay squarely between what neuroscience can do now - and what we want it to be able to do in a short period of time.

As a philanthropically funded organization, its job is to produce a public good. And so they are publishing as they go, they are blogging about their work, they are bringing in the community and sharing the data for their high-impact research.

And it’s led by full-time executives. We had somebody out of Ed Boyden’s lab move from his academic career and come and be CSO and then CEO. They have hired in experts from Janelia, Hopkins, IST Austria, MIT to come do their neuroscience. They have hired automation engineers and barcoding scientists to work collaboratively together towards these end-goals.

We’ve launched ten organizations tackling everything from building tools, datasets, platform technologies, and they’re all sprinting towards their goals.

The blueprint of all of our FROs is trying to unblock those key nodes at the trunk of the tech tree. Let me give you a couple more examples.

Cultivarium is making tools and data accessible through their website and their portal, which is a one-stop shop for biologists looking for information for over 170,000 organisms. Cultivarium is helping scientists figure out how to work with the hundreds of millions of organisms that are available in the ecosystem.

Right now, most R&D in labs and in industry is done only in a handful of organisms rather than working with what is available in the wild, purely because it’s really hard. It took our founders - they worked with one novel organism - it took them their entire postdoc to be able to grow it at all, which means it is inaccessible for people in academic labs or people in industry to make that investment, all to barely be able to get to do the science.

So they’re working on building a set of platform technologies, where you can bring them an organism or a handful of organisms, or you can bring them a use-case that you want to work in, and they can generate how to work with that organism. Recently, they announced a $10m award from the Wellcome Trust, which is dedicating over £50 million in fungal research across their Discovery Research, Climate and Health and Infectious Disease programmes. With this support, Cultivarium is expanding from bacteria to archaea and fungi.

So you can log on to their portal and access their data, go in and explore the tree of life, go read their preprints about the different technologies they have built.

Another FRO is called EvE Bio.

Good science depends on good data, especially in the age of AI. (As we know, not all data is good data!)

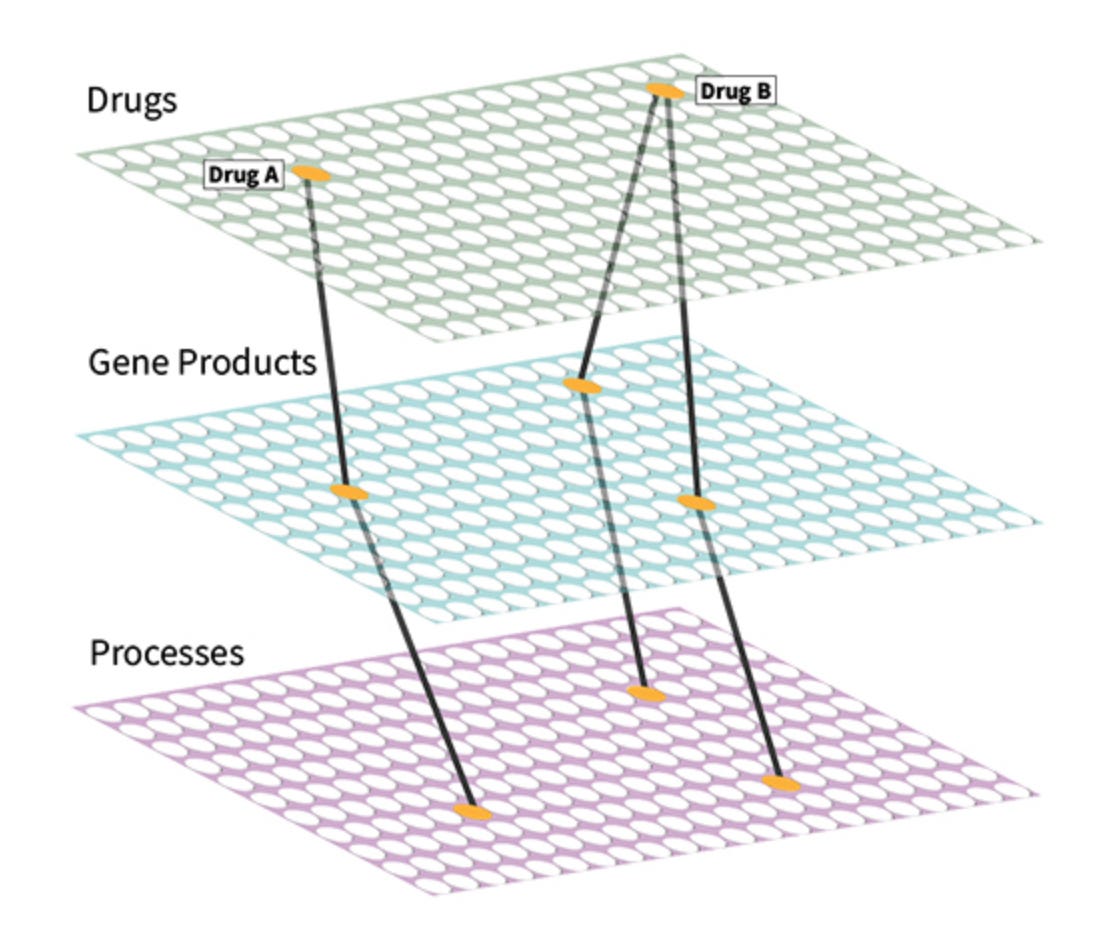

EvE Bio is building a world-leading dataset of the pharmome. They’re taking every single small molecule drug that the FDA has approved that they can get their hands on - there are a couple where you physically cannot get that small molecule - and they are testing them against hundreds of druggable targets, genetic targets in the genome, and they are open-sourcing that dataset. They’ve developed and are running a high-throughput screening assay about every day and a half, and have now screened more of these combinations than anyone else in the world.

And the data is all available online, under a Creative Commons license. You can check out that data at data.evebio.org.

Those are a couple of the new organizations we have launched in the last few years to tackle gaps we’ve identified where fundamental capabilities would unlock transformative new research. Thanks to the support of philanthropists, we’re able to run this major meta-experiment in institution building.

When we started this, my cofounder, Adam Marblestone, would have guessed that there were on the order of ~10 really good low hanging FRO shaped problems out there. And so we started a systematic search for those problems.

We talked to leading researchers in their field and we would say “what would you do with $50 million dollars to fundamentally change your field?”

And they would say “more money for my lab!”

And we would say “OK, but what if you didn’t have to pay new grad students? What if you didn’t have to publish a paper with a grad student every six months? What if you didn’t have to worry about tenure? What if you could build any facility you want? What would you do with $50 million dollars?”

And they said “more money for my lab!”

And then they walked away, and took a shower or took a walk, and they came back later, and they said, “hey, actually, this dataset is fundamental. This microscope would change the way I could look at things. We have a climate modeling project that will unlock the way that we do marine-based carbon removal.”

All of these things took people and scientists asking themselves new questions. Scientists have frequently been asking them the questions that you have the ability to answer. So if you can answer “what is my next grant proposal?” or “where am I going to get tenure?” - those are the questions you ask yourself.

By asking “what would you do with $50 million to fundamentally change your field?”, people are coming up with new answers, and it’s so exciting.

We took that series of conversations and turned it into the Gap Map. We put out a database of what we believed were gaps and missing foundational capabilities across a range of almost two dozen fields of science. And we’ve been pleasantly surprised by the adoption and use of the Gap Map. I’ve had policy makers from DC to Singapore to Berlin tell me that they are using it in their discourse, as they’re trying to think about their strategic avenues.

You can scan this QR code, if you’d like, or find it gap dash map dot org. There’s a download tool available if you want to put it into a model or query it with your AI assistant. We love adding new things to it - this is a collaborative project. So if you have areas that you think would have fundamental gaps or missing capabilities, let us know. If we’re wrong - we really love it when people tell us we’re wrong - please feel free to reach out.

At Convergent, we believe that new institutions and alliances are often the missing piece in solving critical gaps in scientific progress.

FROs are only one way to solve a set of problems that existing institutions - like traditional academia, startups, large corporate, or governmental research centers - cannot address because of their unique institutional incentives.

They are one new type of organizational form for producing scientific public goods. But we are not the only organization building FROs anymore - there’s a new one in the UK called BIND that just launched with Research Ventures Catalyst. We are working with ARIA now to launch one in the UK.

Other people are working to stand up their own FROs. And - I don’t think that FROs are right for every gap, or that all science should be done with an FRO. But I do believe that we’ve prematurely standardized on a set of R&D institutions - this ecosystem has come some way, and we’re really good at doing research, but we’ve left things that are incentivized by other shapes of organizations on the table.

I am so excited to see everyone here really thinking about how to do science better. I’m excited to hear funders and policy makers in the UK and Europe pushing to run experiments about how we fund things and trying new and different ways to practice science.

I’m most excited by new questions that might be answered by new types of organizations. I look forward to joining the Metascience Alliance, a powerful new opportunity to bring together old and new institutions and work towards a better science. That work is critical, because it shapes how we do science during the fastest-moving developmental period in human history. I really think that what we are doing now will impact humanity for the rest of its existence, and those outcomes are dependent on all of us.

So I’d ask you to please, be bold. Take it from me - you don’t need to be limited by what came before, because we can build the institutions and alliances we need, and then we can get to the exciting work of doing science and R&D. Then, we’ll live in a world in which scientific progress is hopefully only limited by the creativity and hard work that we put in.

Good stuff!

In the spirit of things-we-don't-yet-know: the phrase "the brain" here might best be replaced with "the nervous system" (much of which lives outside the brain) to fill out the possibility space.

On that same note: on the same day this was published, we also learned "synapses" might be sometimes replaced with "nanotubes" directly connecting dendrites 🤯

What we need to do: "be bold. Take it from me - you don’t need to be limited by what came before, because we can build the institutions and alliances we need, and then we can get to the exciting work of doing science and R&D"