Announcing Merge Labs

A neurotech FRO takes root

Today, Merge Labs announced its launch as a new research lab pursuing long-horizon R&D in ultrasound-based neural technology, with $252 million in funding from OpenAI, Bain Capital, Gabe Newell, and others.

Merge Labs’ new team and initial technical direction have roots in Forest Neurotech, a Focused Research Organization (FRO). Forest and Merge will continue to partner, carrying forward the transformative vision we shared when we started Forest just a few years ago. We are thrilled by the pace with which Forest was able to prove the efficacy of the FRO model, and that this proof has spurred deep tech investment at the scale required to take it to the next level.

Moving forward, Merge Labs will invest deeply in long-horizon R&D. In parallel, the ongoing nonprofit effort led by Forest will continue to expand scientific partnerships.

Making Waves

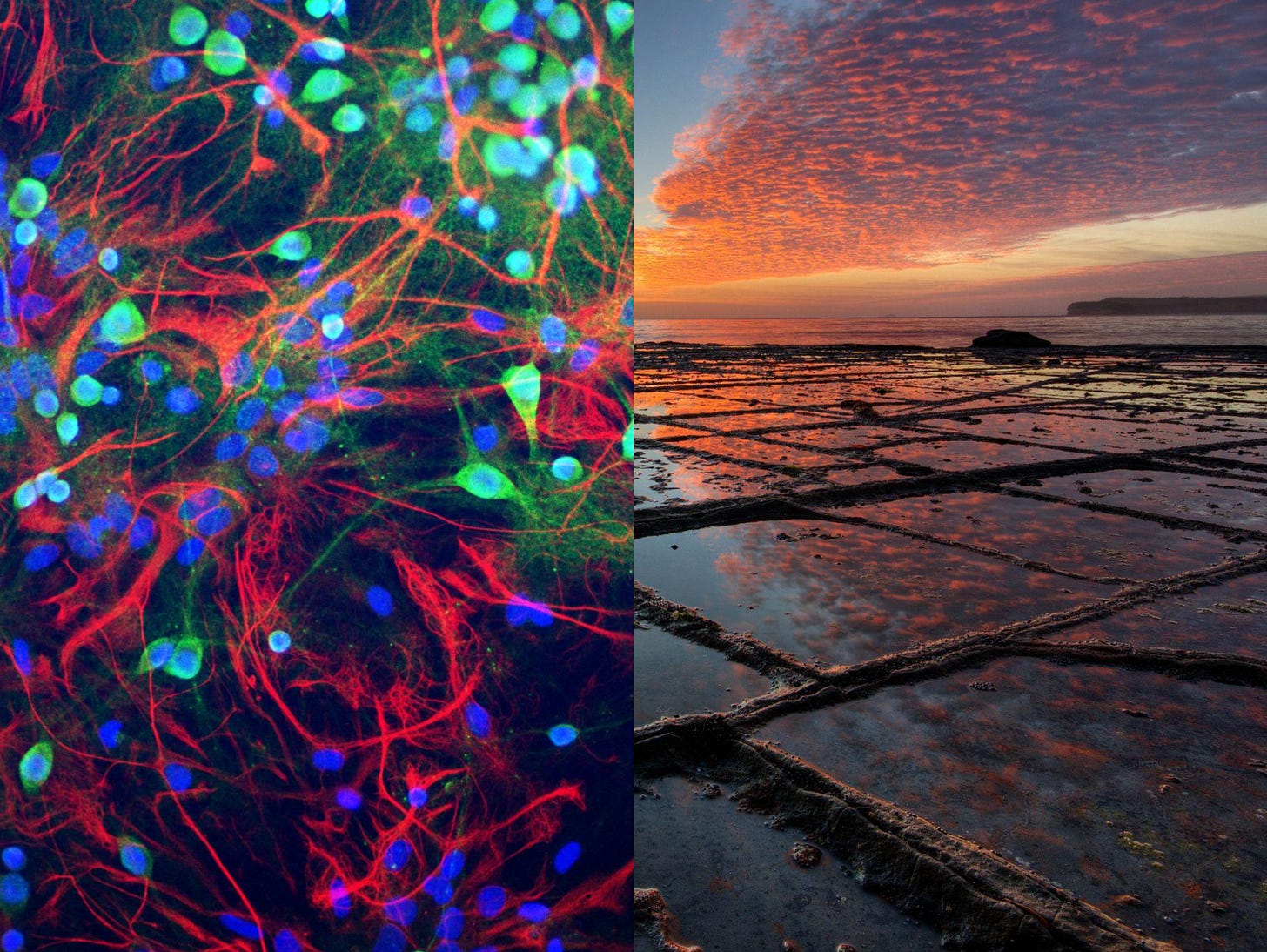

The human brain is a few pounds of soft tissue comprising about one hundred billion neurons (and tens of billions of other cells) packed into an opaque object about a dozen centimeters on each side. Pulses of electricity, a diverse range of chemistries, and dynamic subcellular growths and contractions animate the brain’s connections. These phenomena underlie the entirety of the human experience and make us who we are.

As a result, we’ve built an extraordinary toolkit to measure and stimulate the brain. We put people inside magnetic chambers cooled with liquid helium to infer blood oxygenation (functional MRI); we apply dense electrode arrays to pick up faint electrical signals that have traveled through skull and scalp and propagate across skin (EEG); we shine near-infrared light to estimate blood flow (fNIRS); and, in the highest-stakes cases, we perform neurosurgeries that place electrodes directly on or in the brain to record and modulate activity in patients.

And yet, for something so important, we still have an incredibly limited understanding of how it works, and each of our tools comes with hard tradeoffs.

No single modality hits the “Goldilocks” combination of coverage, resolution, invasiveness, portability, and cost that would make brain interfaces truly transformative.

MRI can be powerful but loud, expensive, and immovable. Electrode placement can be exquisitely precise but invasive, localized, and sparse. EEG and fNIRS are accessible but biased toward signals near the scalp, and they struggle to reach the deep brain regions that shape motivation, sensation, movement, and cognition, and which Adam discussed recently on Dwarkesh Patel’s podcast:

Ultrasound technology works by emitting high-frequency sound waves and listening for the echoes that come back. Some of those waves reflect off hard boundaries, while others travel through softer tissues (like the brain) and scatter off gradients and textures in those tissues. By measuring the timing and strength of the returning waves, we can reconstruct what’s happening beneath the surface. Think of the classic ultrasound image of a fetus and the sound of its heartbeat that gives expecting parents the first picture of their child.

How can this technology help us see what’s happening in the brain?

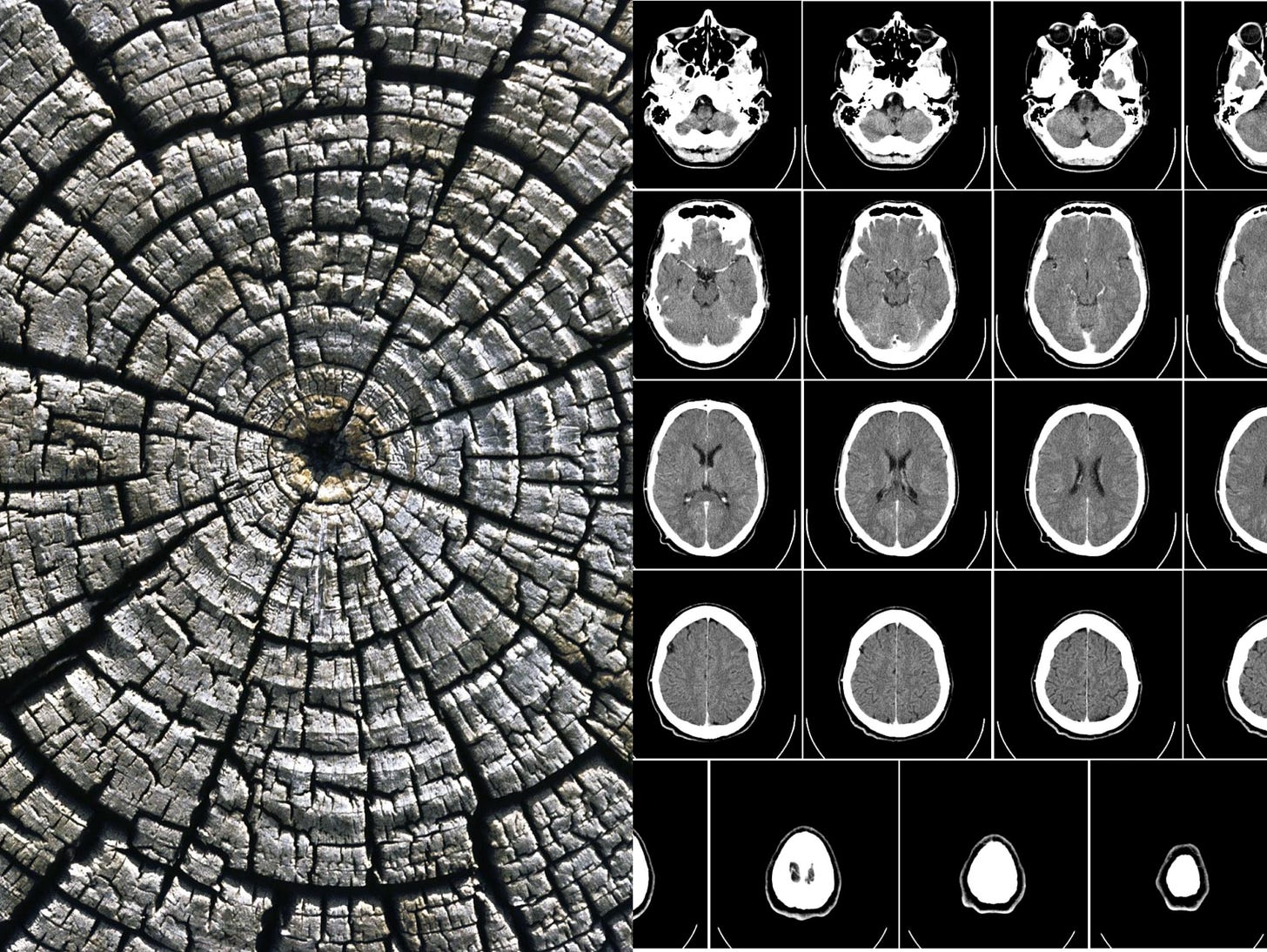

Functional ultrasound imaging is a modality for using these high-frequency waves of sound not only to see biological structures but to get a window into neural function. The physics of ultrasound and its backscatter allow us to produce an image with a resolution that is on the order of a hundred microns in width (with 100 µm being roughly the width of a human hair).

At the same time, what makes ultrasound especially compelling is its field of view. It can cover large volumes, with a field of view that can span from the surface of the brain all the way to its very center. Hence the name “Forest”: ultrasound as a brain interfacing modality uniquely lets us not lose sight of the forest for the trees, nor vice versa. Here’s Sumner Norman, Forest’s founding CEO, describing it on Ashlee Vance’s podcast earlier this year:

While there is no law of physics that rules out ultrasound as a high-resolution readout modality for brain activity, there is one practical obstacle: the thick bone of the human skull. That is why Forest chose to start in cases where a “window to the brain” already existed. In patients who’ve had a craniectomy, usually for relief of swelling or surgical access, Forest was able to deliver clean ultrasound into the brain and recover the highest quality signals possible for scientific discovery. This strategy catalyzed Forest’s ability to demonstrate key milestones for the field: ultrasound can measure function across wide swaths of the human brain, with incredible sensitivity and resolution, on the path to a true whole-brain interface.

Forest’s vision includes many downstream applications: a single ultrasonic implant that can monitor and treat multiple diseases and tackle many use cases, high-performance brain-computer interfaces that don’t require penetrating brain tissue, and one of the most powerful new scientific tools that every clinician and neuroscientist can access.

Fast FROward

Our core thesis for Forest was that raising the bandwidth and coverage of brain interfaces while lowering invasiveness could open up a large design space for clinical and, eventually, broader applications.

It had been theoretically clear for some time that physics permitted such a technology. And when we met the Forest founders, they had already begun to publish papers that demonstrated that the technology could be used to get real, decodable, tractable information about brain activity.

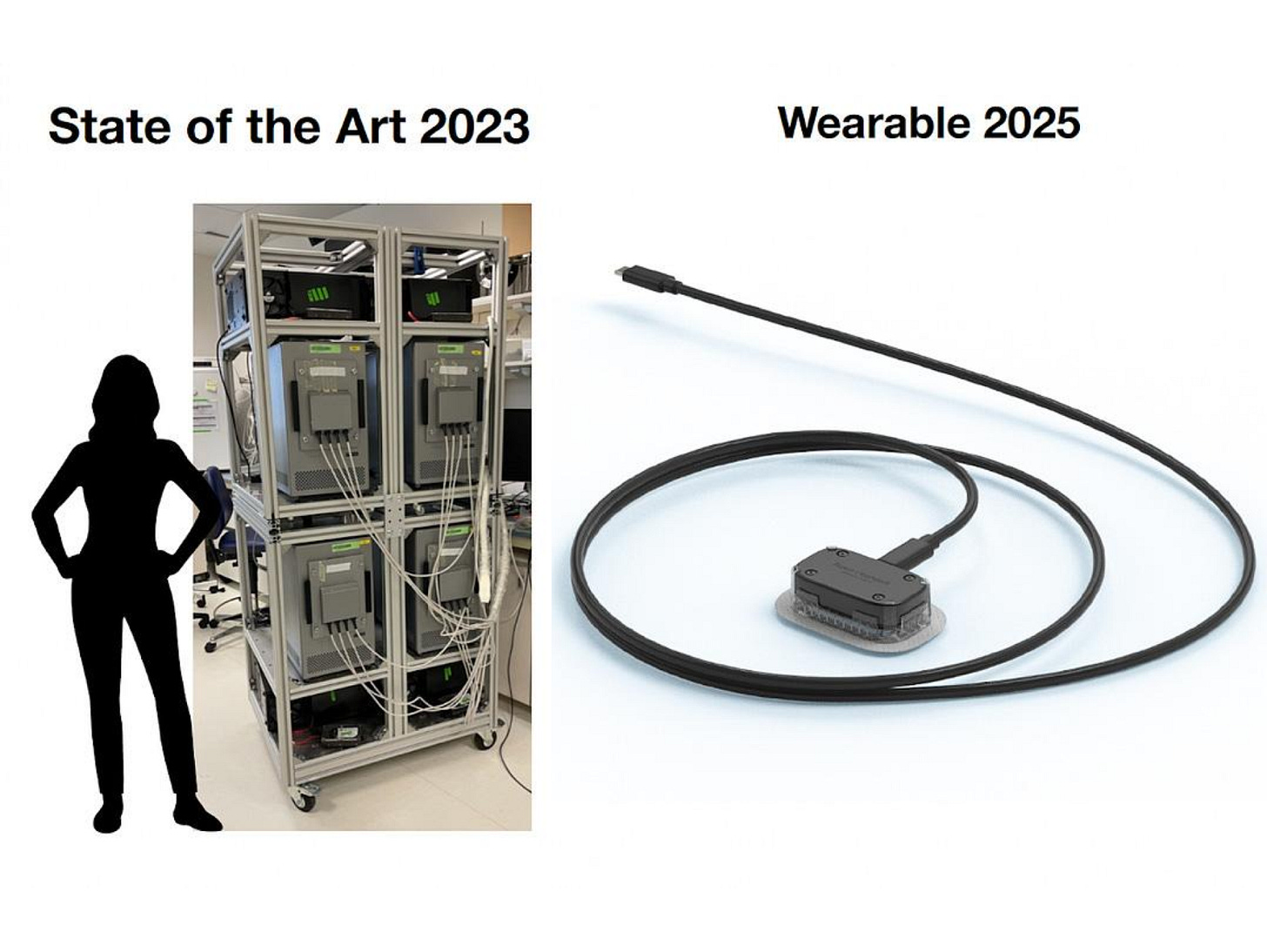

The state of the art in 2023 for this technology was unwieldy, large, and unsuitable for most of the work that clinicians, neuroscientists, and others could hope to use it for. The idea that functional ultrasound imaging in the brain could be usefully done with a small wearable was largely unproven, but plausible in principle.

Before Forest, the view that this was worth pursuing was decidedly not widespread or accepted in the broader neurotech and BCI community. In 2021 it was clear that neither academia nor industry was both able and willing to take a concerted risk on developing this technology.

The Forest founders wanted to make ultrasound a practical modality for next-generation brain sensing and neuromodulation, to ultimately develop a safer, less invasive, and more scalable alternative to what existed, and they sought to make this capability broadly accessible to the neuroscience, neurology, and neuropsychiatry research communities.

We believed those initial physical possibilities of ultrasound could be channeled into useful observational tools and potentially, as ongoing trials funded by ARIA are exploring in the UK, neuromodulation-based therapeutics.

This vision became a reality because of a group of purpose-driven philanthropists – Eric and Wendy Schmidt, Griffin Catalyst (the civic engagement initiative of Citadel Founder and CEO Kenneth C. Griffin), the Riley & Susan Bechtel Foundation, James Fickel, the United Kingdom’s Advanced Research and Invention Agency, and an anonymous donor – whose generous support enabled us to start Forest in 2023 as a Convergent Research Focused Research Organization (FRO) pursuing a clear fundamental capability goal in neurotechnology.

As a FRO, the Forest team developed and pursued an ambitious roadmap for scientific development, software, and hardware advancements. They were dogged in this pursuit, and the improvements they were after came fast: we believe that the Forest device went from lab to human patient in the shortest time ever achieved by comparable neurotech efforts, moving from launch to utilizing devices in patients through multiple IRB-backed clinical pathways in a matter of months.

During their time as a FRO, Forest produced the first-ever functional brain imaging data in humans using ultrasound-on-chip, proving that it can drive a minimally invasive, functional human brain imaging modality.

Forest quickly set up collaborations with clinicians at UCLA Neuro-ICU and Cedars-Sinai, and began demonstrating meaningful capabilities across the tech stack, including ongoing human studies that detected auditory-related signals in traumatic brain injury patients.

And they’ve built a foundation for hardware, software, and signal-processing that is increasingly scalable for trials and clinical use. Last year, Forest released the open-source ultrafast CUDA-accelerated ultrasound beamformer which enabled practical and near-real-time ultrasound data processing for them and their collaborators, and is now available to researchers across the ecosystem. This technology is an order-of-magnitude improvement on the state of the art that came before.

Their early in-human data has shown correlations that meet or exceed published results recorded via fMRI on the same paradigms, strengthening confidence that ultrasound can capture task-relevant functional signals. We believe that this is only the beginning of what can be done with this technology.

A Sonic Boom

We are also deeply motivated by what this technology can mean for people around the world. Millions of people live with severe or treatment-resistant variants of mental illnesses like depression, bipolar disorder, and OCD, meaning that several drugs or treatments failed to provide them with sufficient relief. Billions more people could benefit from a deeper understanding of how the brain works and a greater ability to tune its functioning in health and in disease.

One set of results that we’ve been following firsthand stands out here. As Sumner described on Core Memory this summer, Forest reported bedside detection of “cognitive motor dissociation” (sometimes called “hidden consciousness”) in a comatose patient using ultrasound.

Miniaturized ultrasound is particularly powerful here: it’s impractical and cost-prohibitive to constantly bring comatose patients into the MRI suite from the ICU. A bedside-ready modality for these patients could be revolutionary for our understanding of (and potentially the treatments available for) their conditions, as well as deeply meaningful to their loved ones.

This is just one transformative application among many.

New Growth

We believe that this branching point demonstrates one of many models of success for a FRO.

Forest started as a single organization pursuing deep platform R&D along both a technical development roadmap on the one hand, and what we’d call “impact discovery” on the other. That impact includes public dissemination of the technology, research collaborations and partnerships with clinicians, and practical pathways to getting devices tested and used in medicine. As both the technical milestones and impact proof points began to manifest, we saw new surges of interest in this modality, which we believe will be critical for clinicians and scientists around the world.

We hope to see many more. As highlighted by last month’s Tech Labs Initiative announcement by the NSF, integrated teams pursuing transformative engineering-heavy foundational capabilities with speed and focus can be a powerful way to unlock larger fields. We can’t wait to see how the scaled revolution we dreamt of when we planted the first seeds of Forest continues to grow both through Merge Labs’ work and the ongoing work of the Forest nonprofit.

We are proud of all that Forest’s small, integrated team has accomplished. We congratulate Forest and Merge Labs, and look forward to sharing more about the ongoing Forest nonprofit’s upcoming priorities and leadership here soon.

Incredible! Congrats team

I am a HUGE fan of Convergent Research and an advocate for the FRO model y’all have championed so ably. The work you’ve done has meaningfully expanded the aperture of the types of technosciece that can be funded. Thank you!

But it’s with deep trepidation - and, honestly, sadness - that I read this announcement. Tech investors and funders have a responsibility to our neighbors, society, and future generations to be wise stewards of the scientific enterprise. Our funding decisions shape the direction of science. They nudge the world toward certain futures, and away from others. They are weighty decision!

A world where humans merge with (read: merge into) algorithms is not a world of human flourishing. We should resist it. Not fund it or celebrate it.