The Future of Focused Research Organizations:

Working with Convergent on the NSF Tech Labs Initiative

tl;dr: If you’re drafting an NSF Tech Labs RFI response around a team-built public good that removes a major bottleneck in a field, we’re happy to talk. Convergent has incubated 10+ FROs (and learned a lot in the process) and can help pressure-test whether your idea is “FRO-shaped,” and, if it is, explore partnering (including potentially referencing your team in our RFI as a prospective collaborator). If you’re determined to advance this kind of effort, we have an opportunity to amplify each other’s impact at a uniquely exciting moment for unconventional scientific projects. If this interests you, you can reach us via this form, and read on…

Last Friday, the National Science Foundation released a request for information about the “launch of a new initiative designed to launch and scale a new generation of independent research organizations.”

In their announcement, they wrote that:

The Tech Labs initiative will support full-time teams of researchers, scientists, and engineers who will enjoy operational autonomy and milestone-based funding as they pursue technical breakthroughs that have the potential to reshape or create entire technology sectors. Tech Labs teams will move beyond traditional research outputs (e.g., publications and datasets), with sufficient resources, financial runway, and independence to transition critical technology from early concept or prototypes to commercially viable platforms ready for private investment to scale and deploy.

We’re thrilled that new models for doing vital infrastructure-building for science – including some that may be Focused Research Organizations (FROs) – will be (hopefully!) implemented by the federal government next year.

When we wrote the original blueprint proposing FROs in 2020, we expressed the importance of enabling:

… the U.S. government to fund centralized research programs, termed Focused Research Organizations (FROs), to address well-defined challenges that require scale and coordination but that are not immediately profitable. FROs would be stand-alone “moonshot organizations” insulated from both academic and commercial incentive structures. FROs would be organized like startups, but they would pursue well-defined R&D goals in the public interest and would be accountable to their funding organizations rather than to shareholders. Each FRO would strive to accelerate a key R&D area via “multiplier effects” (such as dramatically reducing the cost of collecting critical scientific data), provide the United States with a decisive competitive advantage in that area, and de-risk substantial follow-on investment from the private and/or public sectors. Some FROs would lay the engineering foundations for subsequent government investment in programs similar in scope to the Human Genome Project.

Since then, Convergent Research has launched almost a dozen of these non-profit startups in the US to build critical infrastructure for science and technology. Just last week, we had a symposium to cap off our first FRO Founder Residency program, powered by ARIA in the UK. And all year, we’ve been working on new FROs in line with our priorities for the Intelligence Age.

The Possibility of Institutional Forms

World War II and the fiery competition of the Cold War gave way to a surge of institutional innovation in American science funding. Overseen by Vannevar Bush’s Office of Scientific Research and Development, the Manhattan Project showed that the government could create a performer that was built-for-purpose: a team assembled to build a specific product and get a specific outcome. With the end of the war and, a decade later, the launch of Sputnik, wave after wave of institutions came on the scene.

These organizations spanned basic and applied research, R&D that was curiosity-driven and motivated by national need, and it took place across public and private labs. During this time, there was also major investment in research at corporate labs. Think of the famed efforts to push the envelope of computing and more at giants like Bell Labs and Xerox PARC.

But after a while, the explosion of new forms just… slowed or contracted. Today, a vast majority of research funding has come to take the form of small project-based grants, to academic faculty PIs working with a handful of students and postdocs in a university, each aiming at their own peer reviewed papers, theses and future small grants.

Universities have been around for a thousand years and may well be around for another thousand. They’re complex institutions with many critical roles in our society. And they will have a meaningful role in shaping this new initiative from the NSF, as well as any parallel efforts at the NIH and elsewhere.

Our existing FROs have often spun out of universities, and they often collaborate closely with them. Some of our FRO founders maintain joint appointments at universities. And all of them consider university researchers to be key users of their technologies and datasets and a source of critical talent, interaction and input.

But a growing consensus is clear: we have tried to make one type of institution be everything for almost everyone and for every problem. Rather than evolving new institutional forms, we spent decades primarily evolving the university.

For a long time, if you were a scientist or engineer who felt a calling to create transformative public goods, the university was your best and most legible home. If you wanted to build something that would outlast a paper and outscale use in a lab - a new instrument, a reference dataset, a platform that makes whole fields cheaper and faster - you still typically had to smuggle it into an institution and grant structure that was optimized for teaching, tenure files, and individual credit for papers. There were exceptions, of course: national labs, a few corporate and philanthropic institutes, the occasional moonshot program. But as a default career trajectory, “doing an ambitious thing in science that isn’t obviously monetizable” typically meant going through the gauntlet of becoming a professor, navigating the university’s incentives, and pushing against the grain, one grant cycle and one grad student/post-doc at a time.

With the emergence of FROs, other new kinds of institutes, and now NSF’s Tech Labs, we now have the possibility to spur on new institutional forms for innovation that can fill precise and important gaps in what the modern academic system offers.

F is for Focused: Avoiding Near Misses

We are especially excited that the Tech Labs Initiative captures the spirit of targeted focus, integrated teamwork and transformative purpose that have animated the first generations of FROs. They write that:

Proposing teams should describe a clear challenge, gap, or bottleneck motivated by practical use considerations that they are uniquely suited to tackle. Successful teams should have a clear vision of how their defined mission is technically challenging, economically significant, and advantageous, and currently unmet by existing funding mechanisms. A proposal should justify why the approach espoused by the Tech Labs program – including dedicated resources for a full-time team of experts – may be uniquely suited to fostering high-impact breakthroughs while addressing the challenge, gap, or bottleneck over several years.

These elements – identification of a gap or bottleneck; a clear vision that is unmet by existing funding mechanisms and team structures; a full-time team of technical and operational/management experts; a transformative technical roadmap to be pursued over a finite time horizon – are exactly what set the FRO apart from other ways of organizing R&D. FROs are by design not just “academia with more cash” nor are they just startups that are funded with public or philanthropic money. We hope that, in the coming expansion of innovative approaches to team-based science, these specific design principles are further developed and experimented on with care.

Put simply: FROs aren’t for everything.

At Convergent, we design our FROs to fill in specific, missing pieces in scientific infrastructure or transformative technology. In each case, this required us extensively mapping the gaps in a particular field, and building up a vision of how the future could be better in a plausible and mechanistic way, a kind of definite optimism.

We spend a great deal of time refining our impact theses and roadmaps, and it has become quite clear that not every problem needs a FRO, and that FROs are not the best solution for many, missing pieces of R&D infrastructure and transformative technology. Accordingly, the Tech Labs RFI does not suggest a replacement for existing work – rather, it carves out a new ecological niche, on the order of 1-2% of the current NSF yearly budget, for specific problems that need a new shape and are transformative for the other 98% if solved.

Accordingly, there are a lot of things we believe FROs are not well-suited for, as seen in the catalog below of near misses. Avoiding these misdirections of effort is what takes up much of our conversation time with proposers who want to start a FRO with Convergent, suggesting that more intuitive or concrete stories and examples may be needed to help people build a concrete mental model of Convergent-style FROs. We’ll be sharing much more of our learnings, but in the meantime, it may be helpful for anyone reaching out to us to check their idea against these common patterns of “near misses”.

“Just do what my lab does, but with more money.”

This approach does not take advantage of the FRO’s independent, non-profit status – for example, the ability to hire engineers or other non-trainee talent at industry wages or do non-publishable work. This also often applies to the idea of converting a lab into a broader “institute”. Sometimes that can be a great thing to do, but it isn’t a FRO.

“Hire 20 of the best researchers and let them work on blue-sky, individual projects in the same building.”

This does not take advantage of multidisciplinary hiring opportunities or the startup-like organizational structure of a FRO, or its laser focus on time-bounded milestones to unlock a very specific bottleneck (what you specifically build).

“Directly work on the biggest intellectual/commercial challenge in the field.”

Ultimately, FROs exist to catalyze problems getting solved – and that is not always the same as directly working on the biggest problem. FROs are justified not by the raw value of their output but by their comparative advantage: doing things academia and industry cannot do.

For example, if the biggest problem in transcranial ultrasound stimulation is identifying its mechanism of action, the right FRO project might be to build hardware, establish experimental protocols, and give them to labs, in order for labs to go figure out the mechanism.

That is not to say that FROs are not working on some of the greatest direct intellectual or commercial challenges in a given field – often, they are – but that this would not be assumed by default.

“Founders and partners don’t pass the police interview test”

Everyone proposing a FRO should be able to describe, independently, the same set of core goals and milestones for the FRO and why they are the right ones; this isn’t just a loose opportunistic collaboration or consortium. FROs benefit from having a unified focus, and that focus needs to be shared by the founders.

“Define the FRO as ‘fill in everything missing in the field’”

This can be too diffuse. You should carve out which part of the field’s needs are specifically FRO-shaped. Other mechanisms (e.g. ARPA programs or academic research can solve for other areas.)

“Lacking the startup non-profit culture and just wanting to be a regular non-profit.”

See for instance this piece for a bit on the elements of being “startup-like”, even beyond the specifics of the FRO model.

“Work on something that requires professional engineering staff and project management, but isn’t transformative or doesn’t unlock one of the top bottlenecks holding back a field”

There are, unfortunately, a lot of projects that require engineering teams that don’t look like self-organized collections of grad students and postdocs, and also don’t return the fund for investors. In a given area, though, there will only be a handful of the most transformative and fundamental bottleneck unlocks that can massively accelerate progress field wide once built and deployed. In neuroscience, for instance, developing technology for mapping the wiring of the brain is a key, fundamental capability that requires tightly coordinated engineering, making it a good fit for a FRO. In contrast, making improvements to any given niche software tool used somewhere in science may be a positive contribution, and may require professional engineering, but often doesn’t justify the resourcing level of a FRO.

“Asking a question versus building something.”

FROs are inspired by the (somewhat apocryphal) quote by Sydney Brenner that “Progress in science depends on new techniques, new discoveries and new ideas, probably in that order.” FROs are not themselves designed to answer a single scientific question. Instead, they are engineering efforts that build something that allows many scientists to ask many questions.

“Being clear why this is not just a startup.”

Many aspects of startups inform the design of FROs, but the key difference is that FROs are driven by a mission to solve a scientific and technical problem to generate public benefit, not by near-term commercial value capture.

The most valuable FRO opportunities often suggest opportunities for startup companies, yet this similarity can paradoxically undercut their prospects for support. Potential supporters are likely to ask, “Why not do a startup instead?”, yet regardless of founding aspirations, a startup’s inherent focus on specific viable products can in some cases turn its effort away from broadly applicable research results. As a consequence, potential startup companies can sometimes cast a shadow over the landscape of research objectives, drawing attention and support away from some FRO opportunities that may promise the greatest and broadest practical applications.

To be clear, we’re very pro-startup. Any project that can achieve its core mission by being a traditional venture-backed startup should do so – we’re specifically interested in those problems where the market alone doesn’t get the necessary fundamental research (and the platform technologies and tools that enable that research) over the hump.

This isn’t to say there aren’t many great platform technology companies, but it also means there are many good FROs that couldn’t be VC backed.

Building Something New

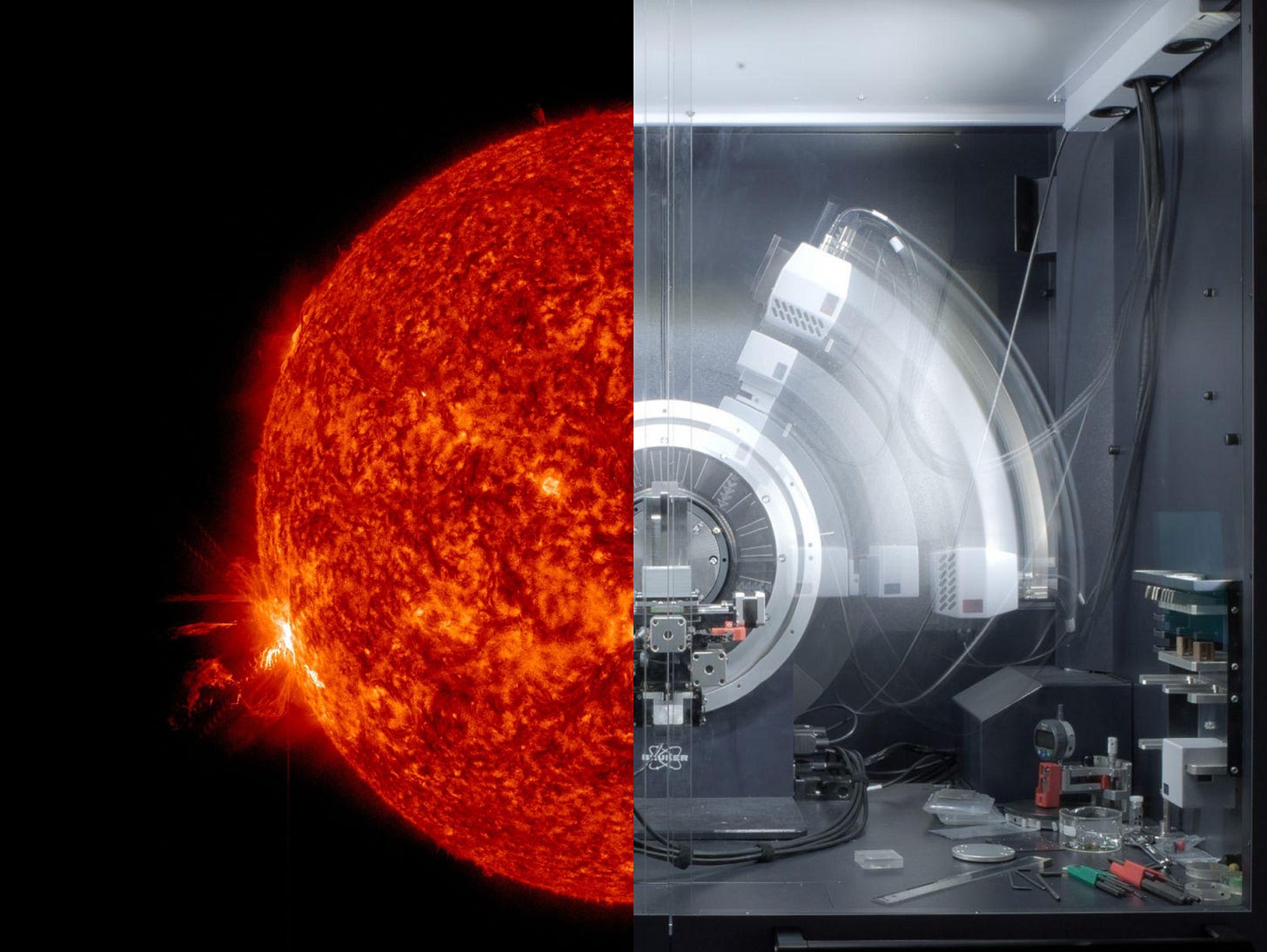

The idea of the FRO is to bring together a big enough team to build a mini-Hubble Space Telescope – a critical mass of well-organized, tightly integrated cross-disciplinary scientific and organizational talent, for a critical duration of time, all pointing at the same target.

Infinite frontiers, serendipitous discovery and novel individual perspectives in science still matter as much as ever – and academic research is a key part of how we get these. But we have overlooked a finite set of gaps that an institutional monoculture has left open for transformation. These are gaps researchers have spent decades feeling, but which they have been unable to cross, for lack of a critical mass of teams organized in truly new forms and incentive structures.

If Tech Labs can help us bridge these gaps, providing new and shared fundamental capabilities for humanity, then we will have made something rare: a new kind of organization that expands the space of possible science for everyone.

How to Work With Us On This

We plan to submit to this RFI, and we hope many, many others do too.

Our sense is that the NSF plans to move fast on this. So: if you have an appropriately shaped idea and nascent team - don’t wait, this is your chance! Read the RFI, attend the webinars, and submit your thoughts on the initiative to the NSF – and hopefully your idea to their subsequent open call for proposals, if they have one.

If you have an idea, but no institutional home (or want to change your institutional home) - you might want to consider working with Convergent Research. As we’re submitting our own RFI, we may list your team in our own RFI submission as such a prospective partner. Please reach out to us to explore this possibility by submitting to this form.

You can see some of our recent priorities here, but we also sometimes think beyond these strict categories.

Structurally, Convergent provides a great deal of support to its subsidiary FROs, ranging from experienced governance and speedy impact-oriented tech transfer, to operational support on non-profit setup, accounting, legal and HR, to a community of other FROs developing an emerging shared practice and culture. We are a 501(c)(3) non-profit separate from any university – but generally excited about working with universities as close collaborators. We were created with the sole purpose of accelerating beneficial science in this way. We’ve stewarded hundreds of millions of dollars of grants already. FROs are set up as LLCs that are subsidiaries of the Convergent parent, but operate with a high degree of autonomy and deep tech startup-like speed. Think of us as a mission control that supports many launches and ongoing efforts. We believe the meta-structure we’ve set up for FROs can, in many cases, help teams align well with the goals of the NSF Tech Labs program. Please feel free to reach out to us to see if our experience supercharging FROs might be a fit for what you want to do.

For your awareness, our FROs tend to involve 4-7 year projects, about 20-30 full-time staff, and about $6-10M/year burn rates, which is on the lower end of NSF’s spectrum; we’re also open to discussing larger projects. To be clear, from our initial read, the Tech Labs RFI suggests a set of possible structures that is compatible with FROs but may also accommodate different or larger projects, inclusive of forms closer to university-adjacent institutes like the Arc or Broad Institutes. We’re especially interested in laser-focused, directed projects to build transformative systems, tools, datasets and so on - what we consider the more “FRO-shaped” end of the spectrum. In the parlance of the X-Labs proposal from the Institute for Progress, we’re an X03 that incubates and supports X02s. We also often do projects well outside the technology areas that NSF’s TIP Directorate is focused on, like our projects in building new tools for astronomy and for fundamental neuroscience. But it is clear that FROs are one of the core types of vehicle this support mechanism is designed to enable, and we’re excited to hear about your ideas for it!

So, feel free to reach out to us at this form. And whether you’re planning on reaching out or going another way, we’d love to add your ideas to our Gap Map.

Amazing post! I found it pretty enlightening. Through multiple examples of what an FRO is not / should not be, it clarifies why it's so challenging for us at ALLFED to define a resilient foods FRO.

It's because “resilient foods” is simultaneously a capability, a portfolio, and a coordination problem. Many plausible interventions sit at different TRLs, rely on different enabling infrastructures (energy, feedstocks, logistics, governance), and only become clearly “the right answer” under a specific catastrophe pathway. That makes it easy to drift into something that looks like a grantmaking program, an advocacy shop, a think tank, or a loose research network. Each valuable, but not obviously an FRO with a tight execution loop.

The post helped me see the core tension clearly: an FRO needs a crisp technical bottleneck and a credible path to direct progress, whereas resilient foods is framed at the level of “ensure humanity can eat even in the worst case scenarios” which is closer to an umbrella goal than a solvable problem statement. If the mission statement is too broad, you can’t pick a single set of milestones; if it’s too narrow, you risk optimizing for a solution that only matters in one corner case.

So the challenge isn’t that resilient foods can’t have an FRO, it’s that it probably can’t have just the one FRO for it. The right move would be to pick a wedge that is (1) catastrophe-relevant, (2) execution-heavy, (3) measurable in outputs, and (4) undersupplied by academia/industry incentives. For example: a validated, regulator-ready “minimum viable diet” ingredient pathway from industrial feedstocks; a modular process package that can be dropped into existing plants; or a supply-chain playbook with testable prototypes (not just scenarios). That kind of scope feels legible as an FRO: specific enough to build, test, and de-risk, while still clearly upstream of the broader resilient-foods portfolio. I'll keep thinking about this.

Thanks so much for sharing this! I completely agree that we need more variety of institutional forms, and I am excited to learn more about the work being done at Convergent Research.

However, I am still struggling to fully understand what types of initiatives are suited for the FRO structure, specifically regarding commercial viability. Tech Labs clearly requires topics to be "economically significant", but the FRO blueprint states that it is for challenges that are "not immediately profitable". So is this model for things that will likely be profitable, but not soon, and investors are unwilling to wait that long? Or does this Tech Labs initiative not quite have the same priorities as FROs?